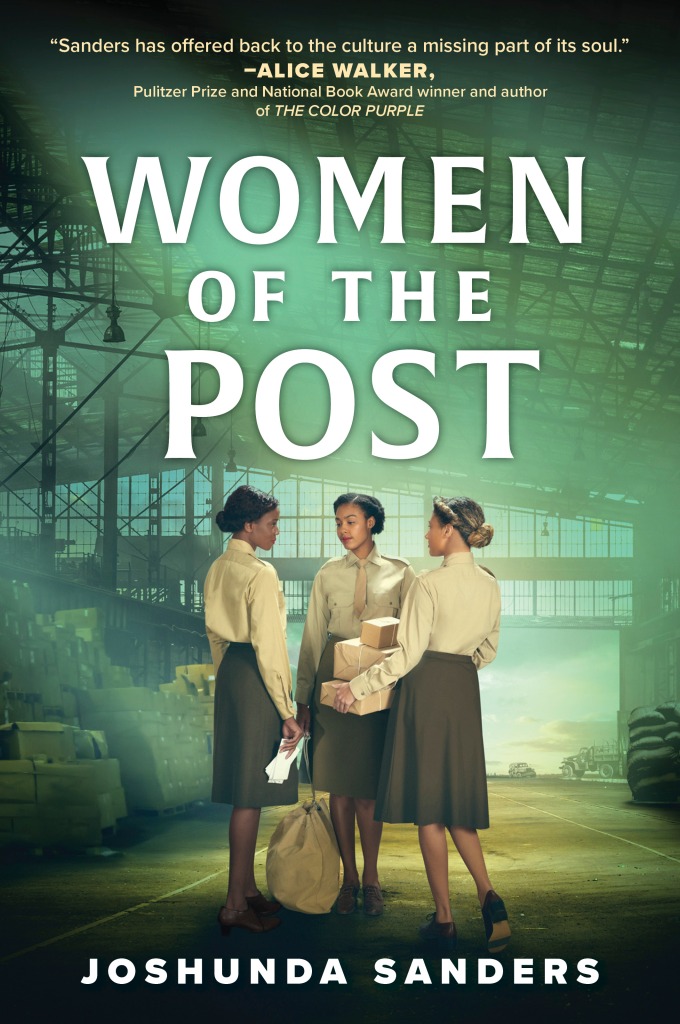

It is with great joy and pride that I share the exciting news that my debut novel, Women of the Post, will be published this summer, in July.

Women of the Post follows Judy Washington from the demeaning work of the Bronx Slave Market to the Women’s Army Corps’ 6888th Central Postal Battalion.

The novel is about Black women’s unvalued labor in the workforce that enabled us to overcome fascism and build morale in order to win one of the most significant wars in American history. It is about how Black women’s love for one another and for our country has been both sanctuary and salvation. It is my love letter to the courage it takes to be unique and also be in sisterhood as you evolve.

I will have much more to say about the book and the process of writing it in the weeks and months and years to come. in the meantime, I hope that you’ll pre-order the book — pre-orders are really important for the success of a book! — which is available everywhere books are sold, including Bookshop or directly from your favorite independent bookstore.