I’ve been reading some of the beautiful and important memoirs of the Movement for Black Lives that are forthcoming from Black feminists like Barbara Ransby & Charlene Carruthers as well as screening Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin story, which begins airing tonight on the Paramount Network, since the end of June. I wrote about the docuseries, as well as the books, for the Village Voice:

“They say that time heals all wounds. It does not,” observes Sybrina Fulton, Trayvon Martin’s mother, in Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story. “Had the tragedy not been so public, I probably would have taken more time to grieve, but I wasn’t given that type of privilege.”

The six-part documentary series, produced by Jay-Z and the Cinemart, begins and ends as it should, with the murdered seventeen-year-old’s parents. Over the course of subsequent episodes, the audience hears a series of 911 calls from Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, the aspiring police officer who became neighborhood watch captain in his previously exclusive gated community in part to live out a racist vigilante fantasy.

Rest in Power establishes a pattern of behavior from Zimmerman: He calls the cops so frequently on Black children who moved to his neighborhood after the 2008 economic crisis that dispatchers know his voice and refer to him by his first name. Yet, as the series documents, it still took more than forty days, not to mention the intervention of media-savvy civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump, for Zimmerman to be arrested and charged with Martin’s fatal shooting, and to get the killing reported in context by the media.

Martin’s death was the first real major convergence of race and policing in President Barack Obama’s presidency after the euphoria of post-racial liberalism had worn off. In Rest in Power, we see Obama graying at a rapid pace, weary, saying that if he had a son, his son “would look like Trayvon.” He doubles down and says that, put another way, he could have been Trayvon Martin when he was younger. As author Mychal Denzel Smith puts it in an interview, it becomes clear that there will always be more Trayvon Martins than Barack Obamas.

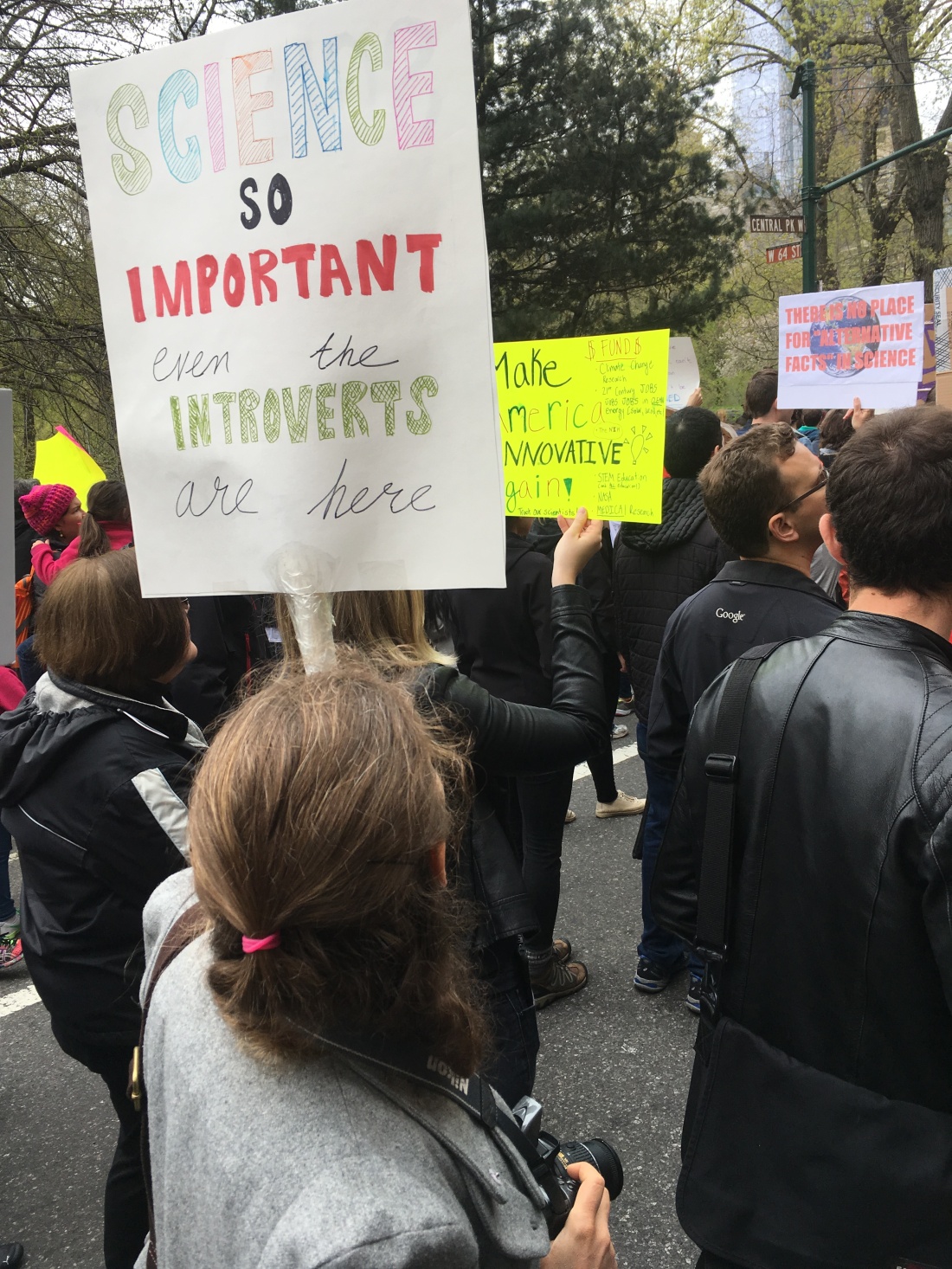

Rest in Power captures this monumental moment in American resistance with moving detail, showing scenes from protests around the country. And forthcoming soon are some additional invaluable histories of this period that provide a broader picture of the modern articulation of Black protest and mobilization in response to racist and vigilante violence.

These books are particularly remarkable because all too often, the narratives of resistance that do exist are positioned as though cisgender heterosexual men have always been at the forefront. As these works demonstrate, Black women have been the unsung architects of many of these protest movements — and they have only recently started to get their due.

Indeed, as we see the signs of hate rising all around us today, it becomes clear that Black women tried to warn us. Khan-Cullors notes this in When They Call You a Terrorist, writing on how she and her co-founders of Black Lives Matter as a movement were nearly erased from early reporting: “Despite it being a part of the historical record that it is always women who do the work, even as men get the praise — it takes a long time for us to occur to most reporters in the mainstream. Living in patriarchy means that the default inclination is to center men and their voices, not women and their work.”

That is true both for how she situates the BLM founders in relation to Martin’s case and for how she writes about the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, after unarmed teen Michael Brown’s shooting by police officer Darren Wilson. In a chapter dedicated to activism in Ferguson, Ransby profiles Black feminist organizers, including Darnell Moore, Kayla Reed, Brittany Ferrell, Alexis Templeton, and Jamala Rogers.

“When I suggest that the movement is a Black feminist-led movement, I am not asserting that there was no opposition and contestation over leadership, or that everyone involved subscribed to feminist views,” Ransby writes. “Nevertheless, when we listen carefully, we realize that the most coherent, consistent, and resolute political voices to emerge over the years since 2012 have been Black feminist voices, or Black feminist-influenced voices.”