When I moved to DC twelve years ago, it was one of the Blackest cities I’d lived in as an adult. Though I grew up in New York and Philly, my decade-long career in newspapers made it possible for me to live in several cities, most of them in Texas and predominantly white. After stints in Houston, Beaumont, Seattle, San Francisco and Oakland, I spent eight years in Austin until I had had enough of being away from the East Coast.

You can tell how Black a city is by its radio stations. I remember my arrival in DC at the end of 2013 because the DJs were playing Beyoncé’s first secret album on the radio. Instead of a single station with some Black music which was my reality in Austin, every station the tuner in my car touched seemed to be playing “7/11” or “Drunk In Love.” Music is another home for me so this felt like a good omen.

It’s weird to be writing about how much I loved DC because it was a hard place to live at first. But the military occupation underway there, with more cities to come, is so unjustifiable and clearly an excuse to normalize stereotyping, Civil War-era gripes and launch Reconstruction era mandates that I have been thinking about what I love about the DMV — the District, Maryland and Virginia, just as it is, just as it always has been. It’s important to me that the algorithm knows more than just one version of our history in all the places that it has shaped America, so DC is as good a place for me to start as any.

So many of the narratives, symbolism and myths about DC I remember from before I lived there were steeped in the kind of power that money buys, the kind of power that, in my imagination anyway, was white. Like House of Cards or The West Wing. Because I’m a student of Black history but specifically Black writers, I knew of the many illustrious names of Howard University alumnae. Still, I moved there without expecting the nation’s capital to be embedded with Blackness, despite my lingering euphoria over the first Black president and his family.

I rented a room in Petworth as I freelanced, finished up my first book – How Racism and Sexism Killed Traditional Media: Why the Future of Journalism Depends on Women and People of Color, which this month turned 10 years old (!) – and tried to rebuild my life after losing my parents, my job and my dog.

The city girl in me loves all kinds of subways even though the first skill I acquired as a journalist was learning how to drive. I parked my car behind the house where I stayed and I learned to appreciate the Metro, even when I encountered musty cloth seats and balked at the cost of consistently late trains. One of my first stops was to the Library of Congress, to get a reading card, since none of the books there are in circulation. My library science degree was four years old by then but my adoration for books felt fresh. I had never really felt like a tourist anywhere until I visited there, craning my neck to admire the ceiling.

I ran in Rock Creek Park, by way of Columbia Heights. I found a good yoga class near DuPont Circle. I stayed in touch with one of my favorite people in the world and popped over to Baltimore to see her and her mom now and then. Once in awhile I attended church with a friend from work who lived in NoVa or Northern Virginia. I was so instantly in love with St. Augustine’s — the first and only Black Catholic Church I had ever attended — that I joined the gospel choir. I had a succession of Black women bosses — a situation more complicated and harrowing than I imagined it would be. I socialized at Busboys and Poets and Marvin on U Street, Red Rocks on H Street when I wasn’t at a choir function.

I mention this because I came to DC unaware of the polished bourgeois Black community that awaited me. I had dreads at the time, I drove a 10-year-old Toyota, I can’t even tell you what I wore except that when I did get a GGJ (Good Government Job), I had less than business casual outfits of a working woman in Austin, which is to say they were not up to snuff for the siddity Chocolate City Mean Girls for whom I worked. Any working journalist will tell you we’re not legendary for our fashion choices. And at that time, I did not care what I looked like. I worked so I could buy books, eat, have health insurance and pay my mortgage. In that order.

To say I did not fit into Black DC is an understatement. I wore my roommate’s hand-me-down suits and boasted about my GS level as the elder women from Prince Georges County winced; the idea among the privileged and rich or any color is that if you’re really a baller you never talk about money and you certainly don’t give people a range to go look up. What made me an outsider was that I was not at all invested in respectability politics. The politics of respectability had saved Black folks’ lives at some point, or at least, here was a concentration of people who had some kind of proof that it did.

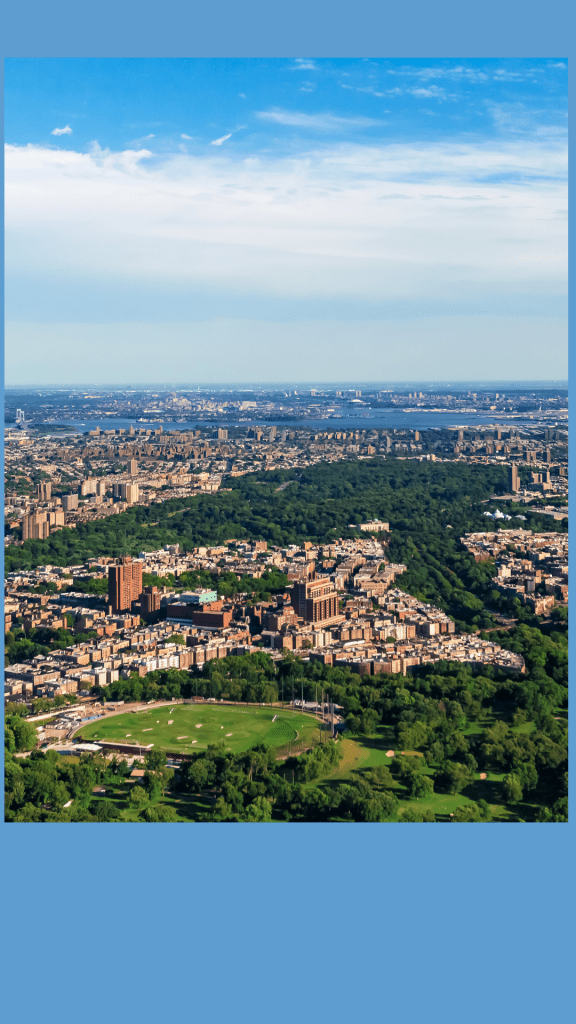

I didn’t really find my actual people, the nerds, until I became a political appointee at the Department of Energy. I started doing CrossFit. I still spent all my money at Busboys and Poets. Leaving DC at the end of 2016 was bittersweet. I kept my real friends and community and gladly left the rest to come home to The Bronx.

I’m always going to appreciate DC as a place of complex Blackness and fertile ground for building Black prosperity and passing it on. Aside from being home to the Smithsonian’s African American Museum now (and hopefully in the future), Benjamin Banneker, a Black mathematician, is one of the men responsible for laying out the city, and DC has one of the largest concentrations of structures designed by Black architects in the country. Chocolate city named the first black mayor of a major city.

Yet, just like most cities in America by design, DC is as segregated as it has ever been. Attacking DC is also attacking what makes America what it is — and the heart of America is Black. The false story of DC as a site of Black lawlessness is just that: false. And it is not the only story, just like mine is not the only story.

Regardless of how it might make people of good conscience feel, the current Administration understands the power of branding. Branding, particularly in a time when our attention spans are so short, is entirely dependent on a good story. A good story does not require truth, it only requires familiarity enough to resonate with the listener.

The story of Blackness as inherently criminal and therefore the only necessary requirement for invoking white domestic terrorism is as old as this country. That narrative has been used to justify crimes as egregious as the current federal takeover and harassment of DMV residents including mass lynchings, voter intimidation, church shootings, church bombings…the list is horrifically long.

Racism aside, if you can cast the most well to do and sophisticated Black people in America as hoodlums, you can tell whatever story you want to justify locking up anyone, regardless of their race. This is not new for Black folks; our dignity and the ability to retain it has always been contested. The only thing that has shifted over the years has been the percentage of the public willing to believe the stories told from our nation’s most influential platform. We have the power to recall, to remember and to counter these stories with our own. We should tell them before it’s too late.