I spend a lot of time with women who are older than me, so it took me a little while to stop joking about feeling old and realize that I actually was starting to feel like one of them.

This mingling with the older crowd started when I was very young. They gave me comfort, guidance. My mother was well past middle age when she had me, and she mustered all the love she had when she could be both physically and emotionally present, but the convergence of those two things only happened infrequently. So I found other ways to get the nurturing I needed.

I found the gaps filled especially by other crones, or elders just a few years older than me. I somehow sensed all along that they were my sister outsiders. At dinner parties or orphan Christmases or birthday gatherings or memorials, to this day, I still find the oldest people in the room to talk to. They settle my spirit, calm my nerves, even when they are chastising me for something or complaining. I am especially in awe of black elders, because it is a miracle to grow elderly and serene and black in America, to thrive and smile and be well, despite the weariness of the years.

I always want to know from them how they got over, how they got through, what they love most about this life they keep living. My heart is always curious about the survivors.

While my mother was older when she had me, her mental state rendered her younger in practice and in practical things like keeping a house, raising a kid, finishing college. The older teachers, strangers and angels I met as a girl and a teenager filled in most of the blanks, as did my older sister, Rita. They gave me, in no particular order: love and life advice, books, encouragement, warm smiles, money for coveted Choose Your Own Adventure or Judy Blume paperbacks at book fairs, used clothes, food for weeks when we didn’t have any in the house, hugs, kisses and a deep, expansive faith in the potential for joy to be a prayer of nourishment that we can live and embody.

They became bridges from despair to hope and faith. Even when I temporarily stopped believing in bridges for awhile. One of the dangers of being self-parented and self-directed, even when you have an old soul, is that you don’t know what you don’t know. The loneliness and alienation, even when it is self-imposed, feels like it could kill you. It is not unlike being a writer and a journalist, this self-direction, in that you are always gathering and storing information to use later.

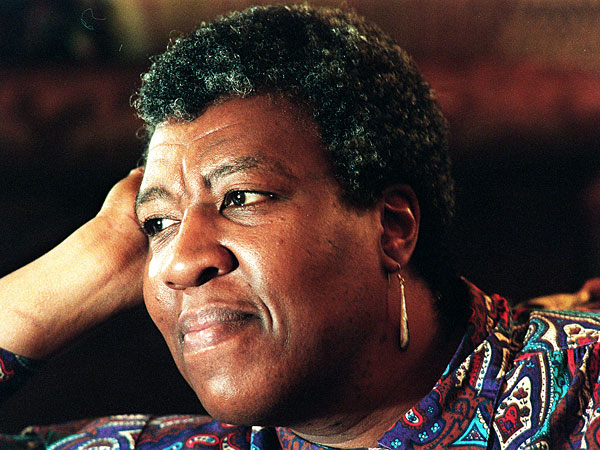

My faith in bridges has always been restored by mentors: Evelyn C. White, Octavia Butler who I adopted as a mentor unbeknownst to her after I interviewed her in 2004 and she told me how much she disliked the phrase ‘Grand Dame’ because it made her sound old and on and on and on. One of the biggest blessings of my life was the ability to say to Alice Walker during and after interviewing her that In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens gave me some important guidelines on how to live, how to be fearlessly myself, how to place my hands in the earth and be restored when I was uncertain about anything else.

These women and many others called behind their shoulders to me on the path and shared the potholes to swerve around: Jealousy, sexism, intimidation, racism. Remember where you came from but know you don’t have to go back; Indeed you may not be able to. Remember how you got here and remember to keep moving forward. Cherish the present. It is all you ever really have.

But the eldest of my mentors, real and imagined, was Amanda Jones. Jones, 109, was the first person I met who made me re-examine what I thought I wanted my life as an elder to be like. When I was younger, I sometimes believed I had all the wisdom I’d need to garner from others, enough to tide me over for the rest of my life. Jones ended my delusion.

She was the granddaughter of slaves and sharecroppers, born just after slavery was outlawed. In the throes of Reconstruction, through witnessing voting rights awarded to women, then blacks, to that moment in which we sat in her tiny living room in Bastrop, Texas, crowded in by the certificates and family photos on the wall that display a life well-lived and well-loved when she could make one of her last efforts on earth to cast a ballot for our first Black President.

I wish that she had said something profound, but the truth is, she was tired. One of her great-granddaughters spoke on her behalf and translated a lot of what she said. This was a woman who slept until 11 a.m. each morning and retired early, too. I smiled, when she grew weary and I thanked her. “I understand,” I added. “If I were 109, I wouldn’t feel like talking much, either.”

What stayed with me most about Amanda Jones was that she had survived so much with her resilient, sweet spirit intact. I saw in her example a woman who had been fully engaged in a life without letting hardship or adversity shape her. I think about her often now, as often as I think about my other friends and mentors, because — as Evelyn once said to me — the older we become the more complex things seem to be.

I saw in her a vision of the old woman I wanted to become — a person whose fundamental nature could not be altered by the overwhelming demands of change or brutality or injustice. I learned from her, too, that such a life, such a presence, did not require anyone’s sign off or approval, merely the understanding that the strength and grace of Black womanhood could serve as an example to the ones coming after us of how powerful one life can be.