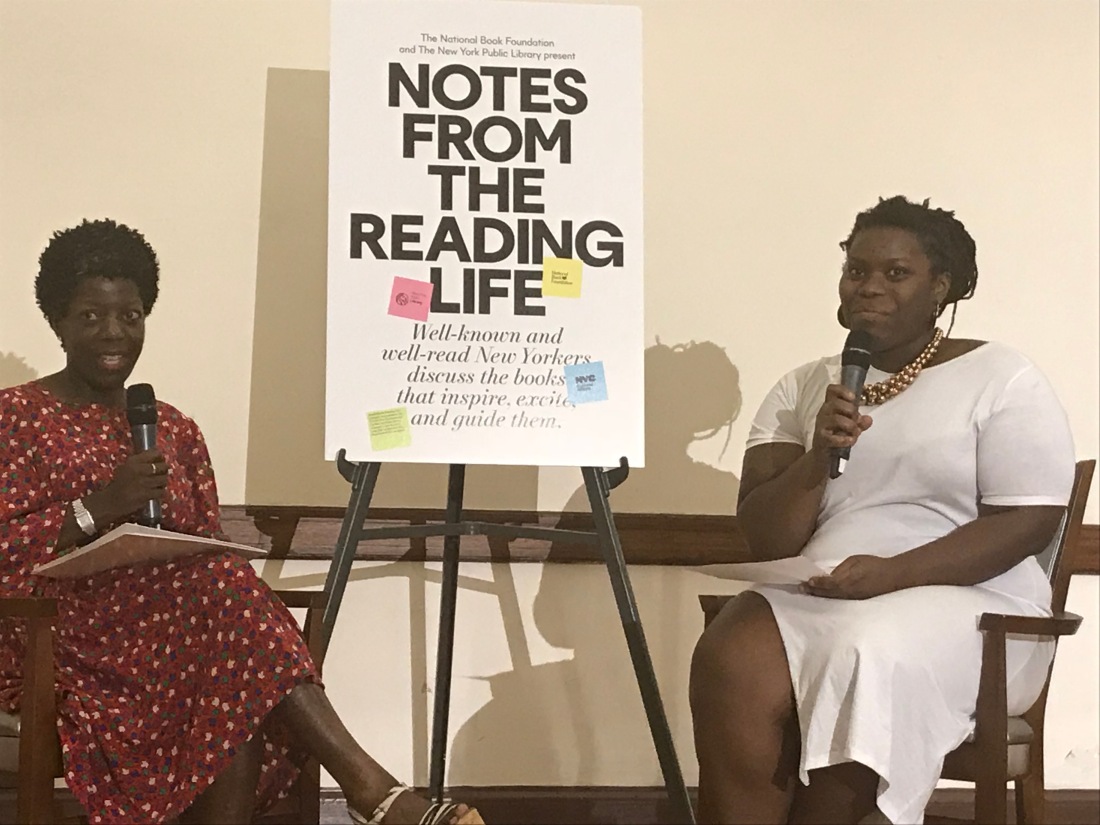

Last Friday evening, I was first in line at the Harry Belafonte Library in Harlem to listen to the first in a series of talks co-presented by the National Book Foundation and the New York Public Library called Notes from the Reading Life featuring two Black women I admire: Thelma Golden and Kaitlyn Greenidge.

Golden has been at the helm of The Studio Museum in Harlem for 17 years, and she is currently serving as Director and Chief Curator. Greenidge is the author of We Love You, Charlie Freeman (and, it must be said, has one of the best Twitter TLs in the game.)

It’s rare that I get to hear two Black women engage in a loving and wide-ranging conversation that centers a Black woman’s engagement with books and reading merely for fun. So of course, I took notes.

The value of attending talks like this is to remember how rejuvenating it is when Black women frame conversation and also how we view story versus how story is framed for us — and frankly, against us. Often, when others are charged with framing aesthetic conversation, in particular, they center themselves and put us at the margins.

For an artist, this makes it hard to invoke the imagination because you never spend any time in a rich, creative or fertile environment. But being in the audience for Golden and Greenidge was one such experience for me.

Golden started by saying she was excited about the renaming of the NYPL branch on 115th street where the talk was held on behalf of Harry Belafonte, and, “to walk in and see the photo of Langston Hughes, to be here in the Alvin Ailey community room — all cultural giants.” And then she underscored that it’s the work of the Studio Museum of Harlem to elevate such giants in ways that often aren’t.

Greenidge started by asking Golden who made her a reader. And Golden mentioned her father, who was born in Harlem, and worked in the building, actually, where the Studio Museum, now is, when it was a bank.

“Arthur Golden was a reader who loved literature. My mother was from Brooklyn. New Yorkers will understand this; when they got married, they compromised and moved to Queens,” she said, to my delight. (It’s hard enough trying to date someone from a different borough I can’t even imagine trying to marry one. Different blog for a different day.)

She described growing up in Queens in a house with what was then known as a den full of books from her father’s library, but no television. He was deeply interested in literature and encouraged her to read.

Her theory is that because she was born in 1965, when he was 40 — considered old for a parent in those days — he let her read anything. Or as she puts it, “We had a relationship to books that was very wide.”

She read both A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones when she was as young as 11, noting with laughter that her mother was very early trying to recruit her to view Brooklyn as the best borough. She read the latter again when she was 16 and again when she was older.

Her mother was from Barbados and grew up in Brooklyn with her siblings in a house purchased by her family in 1926 where some of her relatives still live.

“It wasn’t until I re-read Brown Girl, Brownstones that I really understood my mother and her journey and her quirks,” Golden said. You can think you know about the life of your mother, that it may resemble something that you read in a work of fiction that feels real.

But by reading Marshall’s work, Golden said, “They were all of a sudden actual facts. I asked her later in life, ‘Why did you give me that book?’ She said, ‘I wanted you to understand me better.'”

I don’t imagine I’ll have children of my own, but if that ends up being the path, I imagine this would be such a profound experience…to learn more about the inner life of your mother this way, both in person but also via a book that she loves and gifts to you.

Greenidge said, “I think what you’re describing is the magic of reading for kids. Children can be kind of narcissistic. We think the first time we feel something is the first time its happened.” Golden agreed and expounded on the idea of thinking her experiences were singular and the power of learning they were connected to history.

Which brought us to James Baldwin’s Another Country. (At this point, I admittedly got distracted from the bane of my existence and my lifeline to the world, my smartphone, but I believe I heard Golden said she took a seminar at Smith with James Baldwin when she was student) and he asked her who her favorite character in the novel was. And she said Ida, Rufus’ sister.

I came to quickly enough to hear this gem, “My father went to the same middle school as James Baldwin, and Countee Cullen was their teacher.” (!!)

I was so enamored of this because I have such generational envy for what Harlem was like during the time when Baldwin lived. I know I’m romanticizing it and it was probably as problematic and complex for Black women to navigate emotionally and artistically as every other space is today. But the richness, the products of the period, suggest that the magic had a power that provided at least some possibilities for transcendence. And that’s the part I love and very selfishly wish was still present/actively cultivated for Black writers, at least.

But as Alice Walker has said, We Are The Ones We Have Been Waiting For.

Walker is an example of what it means to be an exceptional living Black woman writer, much like Toni Morrison, the author of another Golden favorite, Sula.

Of all the luscious Morrison books I’ve had the privilege of savoring, Sula falls, for me, just slightly below the Scriptural supremacy and spiritual force in Song of Solomon. But Golden described Sula so poetically, noting that she loved reading it because it was “layered with all the things I know about the world.”

Golden said she never read The Bluest Eye, which is a statement I actually love. Although I did read it, and found that Pecola Breedlove’s envy of blond hair and blue eyes was actually quite resonant for me, I love a contrarian and this assertion (among others) gave me a sense of that streak in Golden. The spectacle of little black girls who hate themselves because they are not white is actually also not the healthiest or most edifying experience for young black girls, so I was happy for Golden, and envious, too, wanting to experience this vicarious liberation from thinking of my beauty in relationship to whiteness and having that praised even from the very beginning — of a life or of a career.

Still, Morrison is not only America’s greatest living novelist, but she is the originator of our current Black literary renaissance, insofar as writers like myself, readers like Golden and almost every Black woman writer I’ve ever known or met who perseveres through self-doubt and the other perils of the writing life have uttered and taken to heart Morrison’s words, “If there’s a book you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

“That informs my work as a curator, to provide room for so many artists of African descent, to make art to allow us into space,” Golden said. “Toni Morrison is, to me, a rigorous example of Black genius.”

The last of Golden’s favorite books she discussed with Greenidge were The Collected Autobiographies by Maya Angelou and Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

It was nice to be reminded of Maya’s habit of keeping a hotel room in any city in which she visited, so that she could write without interruption, accompanied only with “two books, a bottle of sloe gin and a deck of cards,” Greenidge informed us.

Angelou’s work in memoir was the first instance of showing Golden, she said, “the stories we create of ourselves…the importance of the creation of our artistic selves. We get to make for ourselves a world that doesn’t make space for us.”

As for Americanah, Golden’s husband is Nigerian and lives in London. Along with the work that she leads and is invested in, she’s tied to Africa, then, “not just in the past, but also art, culture and ideas in the present.”

As a result, she said that she “felt profoundly seen,” by Americanah, in the same way she did by Zadie Smith’s On Beauty. “It’s what happens when outsiders look at your culture.”

Other notable aspects of the talk included the following:

- When Greenidge asked Golden which book she would give to a small child if she had to, she mentioned Whistle for Willie by Ezra Jack Keats.

- She recalled someone giving her a copy of Invisible Man and finding it formative. She mentioned that someone should write a biography of Ralph Ellison’s wife, Fannie Ellison — do your thing, Internet!

- Since we were in Harlem, and Golden had made note of the pictures of Langston Hughes and other cultural giants of the neighborhood earlier, Greenidge mentioned the I, Too Arts Collective the literary nonprofit helmed by author Renee Watson that has continued to do God’s work preserving Langston Hughes’ brownstone and has transformed it into a site of community for writers of color. “I wish it had not been so hard. I wish it had been a natural act. So much of history is not in buildings. It’s in the neighborhood. I hope that while we continue to move toward our future, that we can continue to honor our past. This is a community with a deep and rich history. This wasn’t just a setting for great work. This neighborhood created opportunity for artists. I hope we can preserve that in ways that people will be able to touch and feel in the future.”

You should go to some of the future Notes from the Reading Life events if you’re in New York or if you’ll be in town for one that’s upcoming. Tonight, it’s a conversation between Tim Gunn & Min Lee. I’m so sad to say I’ll miss the conversation (in the Bronx!) between Desus Nice & Rebecca Carroll at the Bronx Library Center on June 15th — but you shouldn’t.