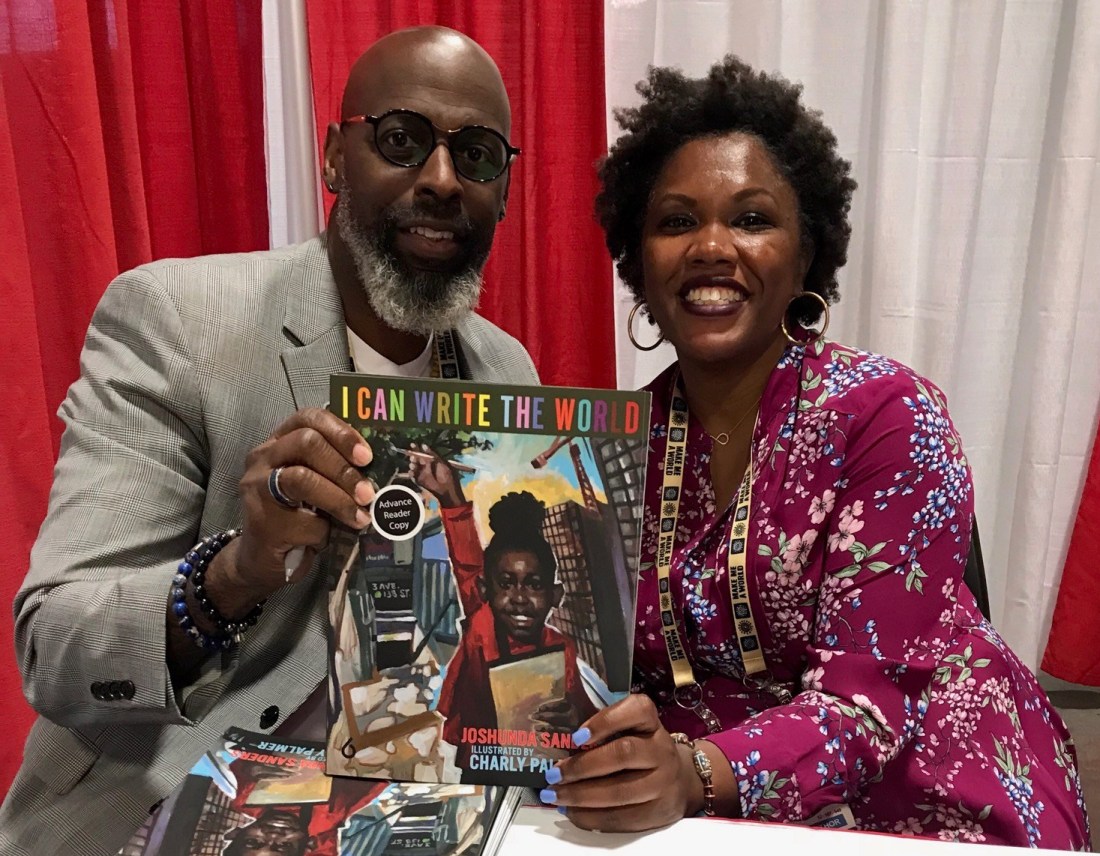

Before I was a journalist, my favorite non-fiction writing and non-journaling activity was to attend readings or lectures featuring Black authors and take copious notes. So it is a kind of coming full circle that I’ve started a Substack newsletter focused on book reviews related to books for and by Black people, Black Book Stacks. (About a year ago, I started a YouTube channel of the same name, which you can view here and if I have a Bookshop store you can find here.)

I always had the innate sense that being a writer was not just about putting words to paper and hoping that others would read those words. I was always searching to put the words I wrote into a tradition. Writing was another way of trying to belong and to solidify a place for myself in a world that seemed bent on my erasure or destruction.

I have vivid memories of a small royal blue Mead notebook that was thick as a brick. I carried it with me to the old Barnes & Noble on Astor Place, through Washington Square Park, up to Emma Willard and Vassar. I had the privilege of listening and trying to absorb the wisdom of Jamaica Kincaid, Gloria Naylor, Janet McDonald, Elaine Brown and so many others. I was a careful collector of Black women writers’ quotes, usually because I couldn’t afford to purchase books of my own and I didn’t not want to vandalize library books. Quotes were the happy compromise; they were short enough for me to carry wherever I went. These were the breadcrumbs and manna they left for me in a trail to who-knew-where but I gobbled them up. Every nugget was a jewel in my crown.

As I made my way in journalism, it became harder and harder for me to give myself permission to keep up this witnessing practice in the same way. Mostly because of time, but also because I realized that such forums and opportunities to hear Black writers and share space with them were fewer in other states and cities. It just so happened that reading the work of Black women in particular was my self-paced MFA program. Sometimes, I had the opportunity to profile, interview and write about them, as was the case with Octavia Butler in 2004 and Alice Walker around the same time. But mostly, I was just glad to have their work to sit with and revel in.

Over the years, I’ve continued to focus my attention on the work of Black writers because, as more of the world knows now, we live in a world where white supremacist capitalism means that what is considered valuable is everything but Blackness or real intimate discussions of all its flourishing contours in spite of and beyond the gaze of the consumption of white people. What I mean to say, I think, is that Black literature has always been a miracle to behold. In part because it comes from a people who have a shorter lineage in the Americas of thriving in literature because of the legal restrictions that forbade them to read and write. Our resilience and perseverance and faith, all bound up in the Word, continued both in an oral tradition and on paper.

The overcorrection here, I’ve found, is that when it comes to fair critique or evaluation of the work of Black writers, is that our books are either ignored, as if they never happened, especially beyond the date or week of their publication, or they are elevated as neutral objects for sale without a real analysis of them and their context. That’s what my new newsletter is aiming to help create in the world. I hope that if that sounds of interest to you, that you’ll subscribe. Looking forward to seeing you on the list.